Ranch Report: B.H. Warnock, the last bad ass west of the Pecos

He lived a charmed life that most only dream of

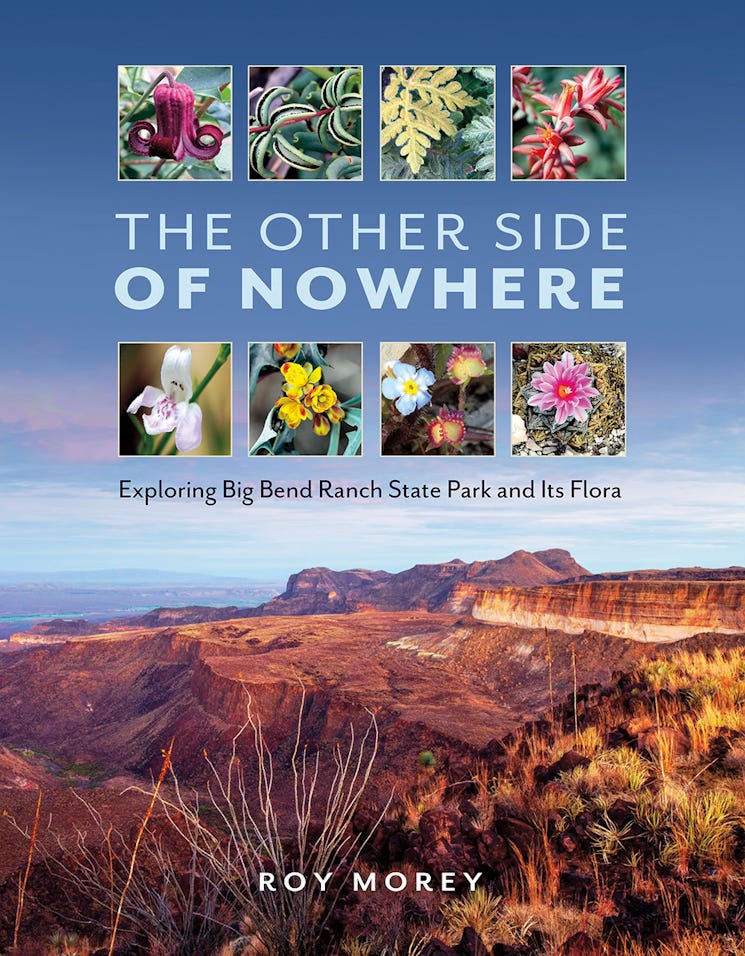

When I received a copy of the new book, The Other Side of Nowhere, I immediately pulled it open to see if there was any mention of my late uncle, Barton H. Warnock, or “B.H.” as everyone in the family called him.

Yes, there he was, prominently in the index and throughout the book. Early on the author, Roy Morey, had a shot of one of the plants named after B.H. the “Warnock’s Water Willow.”

That is one of four plant species named in his honor, and all were named by former students or associates of his. He didn’t name a single plant after himself.

There is even a cactus named after him that grows in Big Bend National Park.

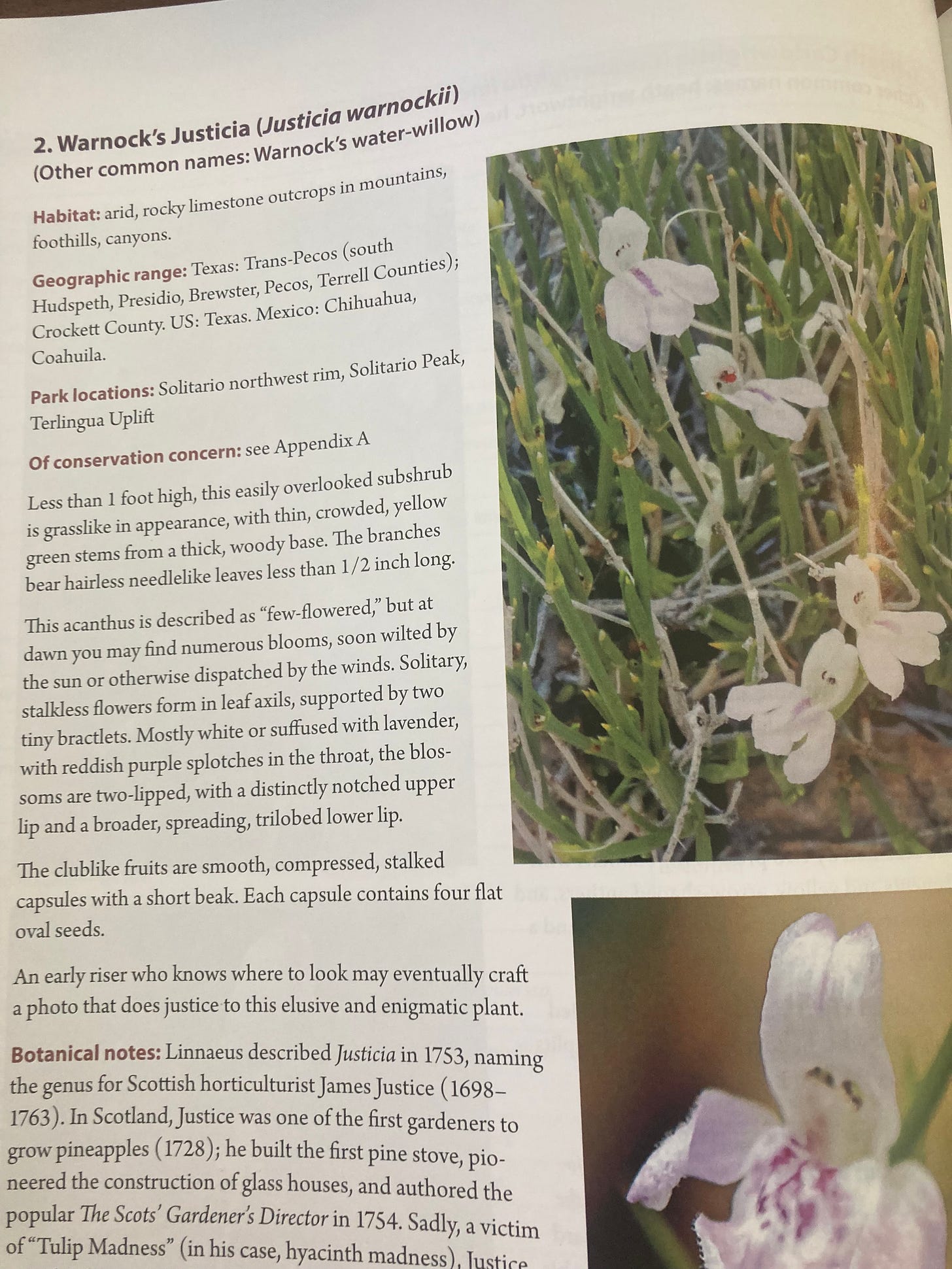

For his entire life, everyone who lived west of the Pecos River knew his name. People flocked to Sul Ross University in Alpine to study under him. But he first gained fame as a stud, high-school-football running back at Fort Stockton high school , then in college at Sul Ross State University, where he still holds the school record for longest TD run from scrimmage, 95 yards!

B.H. in his Sul Ross football uniform. (This was in the leather helmet days!)

His high school peers told me he could “run like a deer” and he once returned a kickoff for a TD against McCamey that won the game. Yet despite his rugged good looks and football player demeanor, he was a curious intellectual, who became fascinated by the plants that grew out in the Big Bend. He devoted his entire life to finding, cataloging and discovering them in this remote area of Texas. (This alone was “going against the tide”. In far west Texas a young man either did ranch work, or got a job in the oil fields.)

After high school he went to Sul Ross State College (as it was called then) on a “work studies program.” He explained to me that they didn’t have athletic scholarships back then, but if he played football they took care of his tuition.

It was during this time (1938) that the Federal Government purchased what would eventually become Big Bend National Park. Once they bought it, the Feds wanted an inventory of just what they had acquired, so they sent Ross Maxwell and four graduate students from Sul Ross to live in some World War I surplus barracks and inventory EVERYTHING. One student cataloged the fauna (animals), another the geologic formations, another the historic sites, and B.H. the flora, or plants. For nearly two years he roamed the future park land gathering four samples of every plant. He hiked, rode mules, or drove in a Jeep with Ross Maxwell over nearly every square foot of the place.

One day the group hiked along the top of Santa Elena Canyon, but ran out of water. They were forced to drink from potholes in the rock, and all of then came down with dysentery. The next morning Maxwell told me that B.H. was the only one who showed up at work. Everyone else was in the throes of diarrhea. “He’s a tough cookie,” remarked Maxwell.

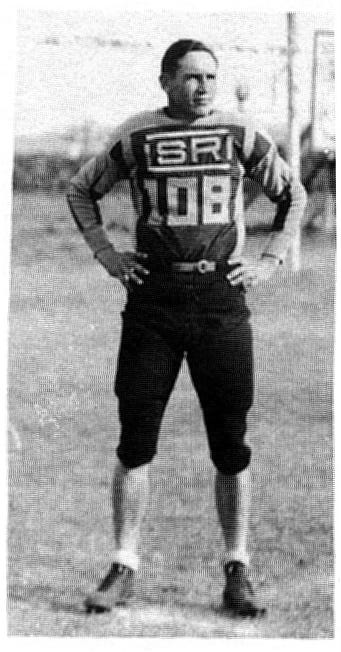

During his time at Sul Ross, B.H. studied under Dr. Omer Sperry, the father of famed Texas horticulturist Neil Sperry. When Big Bend National Park finally opened, B.H. was photographed with Dr. Sperry up in the stone cabins in the Chisos Basin.

B.H. with Omer Sperry up in the Chisos Basin, 1947.

During his more than 35 years teaching at Sul Ross, nearly everyone in the Big Bend (Marfa, Alpine, Fort Davis, Fort Stockton) took his class in botany and went on field trips with him down to Big Bend National Park.

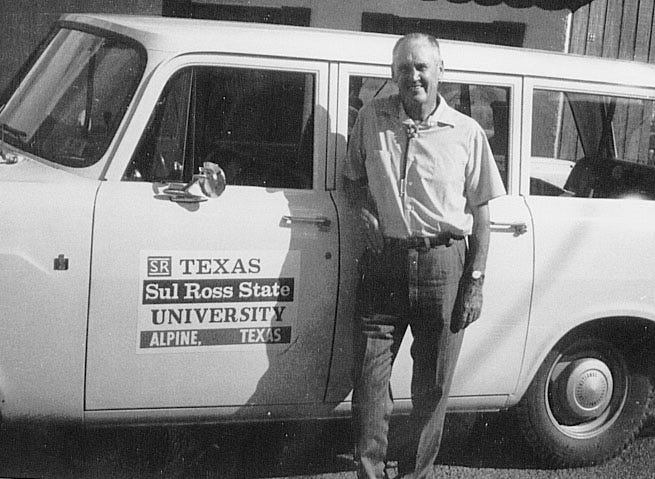

B.H. with his Sul Ross truck during his tenure as a professor there.

For almost my entire life, if I met anyone out here, and they heard my last name, the first question was always, “Are you related to Dr. Warnock?” After answering “yes,” they always responded, “I took his class at Sul Ross.”

Ric LoBello, the superintendent at Carlsbad Caverns National Park, once told me, “The reason I enjoyed studying plants is because unlike wildlife, plants don’t move.”

B.H. wrote what is considered the Bible of Big Bend botany, Wildflowers of the Big Bend Country. Long since out of print, it is much sought after and brings a premium price.

For more than 35 years he taught classes at Sul Ross and led regular field trips into Big Bend. I went with him on two of these. It was a visit to places I never knew existed. One was to the Mariscal Mine, a huge, abandoned mercury mine out in the middle of nowhere. My Buddy magazine boss, Stoney Burns came with me on this trip because he was a nut about the Big Bend and knew about B.H.

Stoney Burns at the Mariscal Mine back in 1978.

But his biggest opportunity came in the mid-70s when he was eating lunch down in Lajitas one day and a man named Walter Mischer joined him. Mischer was developing his resort, Lajitas on the Rio Grande, that he was billing as “the Palm Springs of Texas.” He hired B.H. to develop a museum and collect plants for the arboreteum located in the center of it. It was called the Lajitas Desert Museum.

Decades later Mischer sold his holdings to Texas Parks and Wildlife for the creation of the largest park in the state, Big Bend Ranch State Park.

In his honor, the state of Texas named the visitor center after him. My brother Miles and I came in for the dedication.

Miles, B.H. and me at the dedication of the Barton H. Warnock center

Years earlier, Sul Ross University had formally named the Science Building on its campus the Barton Warnock Science Building. As former Big Bend National Park superintendent Jim Carrico said, “B.H. is the only man I know who has two buildings in Brewster County named after him.”

The Barton H. Warnock Science Building on the campus of Sul Ross State University.

It’s even more amazing when you realize that unlike in most public spaces, he didn’t donate millions of dollars to get those naming privileges. (See Klyde Warren Park in downtown Dallas for proof of this.)

The state of Texas and Sul Ross named those places after him not because B.H. threw them a wad of money, but because he was such a bad ass that his accomplishments spoke for themselves.